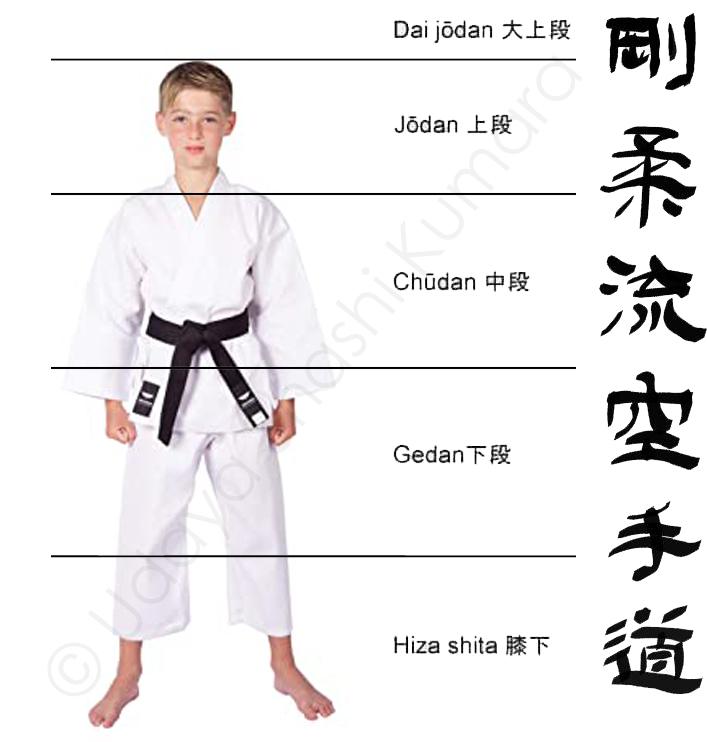

Aikido Training In aikido, as in virtually all Japanese martial arts, there are both physical and mental aspects of training. The physical training in aikido is diverse, covering both general physical fitness and conditioning, as well as specific techniques. Because a substantial portion of any aikido curriculum consists of throws, beginners learn how to safely fall or roll. The specific techniques for attack include both strikes and grabs; the techniques for defense consist of throws and pins. After basic techniques are learned, students study freestyle defense against multiple opponents, and techniques with weapons. Fitness Physical training goals pursued in conjunction with aikido include controlled relaxation, correct movement of joints such as hips and shoulders, flexibility, and endurance, with less emphasis on strength training. In aikido, pushing or extending movements are much more common than pulling or contracting movements. This distinction can be applied to general fitness goals for the aikido practitioner. In aikido, specific muscles or muscle groups are not isolated and worked to improve tone, mass, or power. Aikido-related training emphasizes the use of coordinated whole-body movement and balance similar to yoga or pilates. For example, many dojos begin each class with warm-up exercises (???? junbi tais??), which may include stretching and ukemi (break falls). Roles of uke and tori Aikido training is based primarily on two partners practicing pre-arranged forms (kata) rather than freestyle practice. The basic pattern is for the receiver of the technique (uke) to initiate an attack against the person who applies the technique—the ?? tori, or shite ?? (depending on aikido style), also referred to as ?? nage (when applying a throwing technique), who neutralises this attack with an aikido technique. Both halves of the technique, that of uke and that of tori, are considered essential to aikido training. Both are studying aikido principles of blending and adaptation. Tori learns to blend with and control attacking energy, while uke learns to become calm and flexible in the disadvantageous, off-balance positions in which tori places them. This "receiving" of the technique is called ukemi. Uke continuously seeks to regain balance and cover vulnerabilities (e.g., an exposed side), while tori uses position and timing to keep uke off-balance and vulnerable. In more advanced training, uke will sometimes apply reversal techniques (??? kaeshi-waza?) to regain balance and pin or throw tori. Ukemi (???) refers to the act of receiving a technique. Good ukemi involves attention to the technique, the partner and the immediate environment—it is an active rather than a passive receiving of aikido. The fall itself is part of aikido, and is a way for the practitioner to receive, safely, what would otherwise be a devastating strike or throw. Initial attacks Aikido techniques are usually a defense against an attack, so students must learn to deliver various types of attacks to be able to practice aikido with a partner. Although attacks are not studied as thoroughly as in striking-based arts, sincere attacks (a strong strike or an immobilizing grab) are needed to study correct and effective application of technique. Many of the strikes (?? uchi?) of aikido resemble cuts from a sword or other grasped object, which indicate its origins in techniques intended for armed combat. Other techniques, which explicitly appear to be punches (tsuki), are practiced as thrusts with a knife or sword. Kicks are generally reserved for upper-level variations; reasons cited include that falls from kicks are especially dangerous, and that kicks (high kicks in particular) were uncommon during the types of combat prevalent in feudal Japan. Some basic strikes include: 1. Front-of-the-head strike (???? sh?men'uchi?) a vertical knifehand strike to the head. In training, this is usually directed at the forehead or the crown for safety, but more dangerous versions of this attack target the bridge of the nose and the maxillary sinus. 2. Side-of-the-head strike (???? yokomen'uchi?) a diagonal knifehand strike to the side of the head or neck. 3. Chest thrust (??? mune-tsuki?) a punch to the torso. Specific targets include the chest, abdomen, and solar plexus. Same as "middle-level thrust" (???? ch?dan-tsuki?), and "direct thrust" (??? choku-tsuki?). 4. Face thrust (???? ganmen-tsuki?) a punch to the face. Same as "upper-level thrust" (???? j?dan-tsuki?). Beginners in particular often practice techniques from grabs, both because they are safer and because it is easier to feel the energy and lines of force of a hold than a strike. Some grabs are historically derived from being held while trying to draw a weapon; a technique could then be used to free oneself and immobilize or strike the attacker who is grabbing the defender. The following are examples of some basic grabs: 1. Single-hand grab (???? katate-dori?) one hand grabs one wrist. 2. Both-hands grab (???? morote-dori?) both hands grab one wrist. Same as "single hand double-handed grab" (?????? katatery?te-dori?) 3. Both-hands grab (???? ry?te-dori?) both hands grab both wrists. Same as "double single-handed grab" (????? ry?katate-dori?). 4. Shoulder grab (??? kata-dori?) a shoulder grab. "Both-shoulders-grab" is ry?kata-dori (?????). It is sometimes combined with an overhead strike as Shoulder grab face strike (?????? kata-dori men-uchi?). 5. Chest grab (??? mune-dori or muna-dori?) grabbing the (clothing of the) chest. Same as "collar grab" (??? eri-dori?). Basic techniques The following are a sample of the basic or widely practiced throws and pins. Many of these techniques derive from Dait?-ry? Aiki-j?jutsu, but some others were invented by Morihei Ueshiba. The precise terminology for some may vary between organisations and styles, so what follows are the terms used by the Aikikai Foundation. Note that despite the names of the first five techniques listed, they are not universally taught in numeric order. 1. First technique (?? (?) ikky??) a control using one hand on the elbow and one hand near the wrist which leverages uke to the ground. This grip applies pressure into the ulnar nerve at the wrist. 2. Second technique (?? niky??) a pronating wristlock that torques the arm and applies painful nerve pressure. (There is an adductive wristlock or Z-lock in ura version.) 3. Third technique (?? sanky??) a rotational wristlock that directs upward-spiraling tension throughout the arm, elbow and shoulder. 4. Fourth technique (?? yonky??) a shoulder control similar to ikky?, but with both hands gripping the forearm. The knuckles (from the palm side) are applied to the recipient's radial nerve against the periosteum of the forearm bone. 5. Fifth technique (?? goky??) visually similar to ikky?, but with an inverted grip of the wrist, medial rotation of the arm and shoulder, and downward pressure on the elbow. Common in knife and other weapon take-aways. 6. Four-direction throw (???? shih?nage?) The hand is folded back past the shoulder, locking the shoulder joint. 7. Forearm return (???? kotegaeshi?) a supinating wristlock-throw that stretches the extensor digitorum. 8. Breath throw (???? koky?nage?) a loosely used term for various types of mechanically unrelated techniques, although they generally do not use joint locks like other techniques. 9. Entering throw (???? iriminage?) throws in which tori moves through the space occupied by uke. The classic form superficially resembles a "clothesline" technique. 10.Heaven-and-earth throw (???? tenchinage?) beginning with ry?te-dori; moving forward, tori sweeps one hand low ("earth") and the other high ("heaven"), which unbalances uke so that he or she easily topples over. 11.Hip throw (??? koshinage?) aikido's version of the hip throw. Tori drops his or her hips lower than those of uke, then flips uke over the resultant fulcrum. 12. Figure-ten throw (???? j?jinage?) or figure-ten entanglement (???? j?jigarami?) a throw that locks the arms against each other (The kanji for "10" is a cross-shape: ?). 13. Rotary throw (???? kaitennage?) Tori sweeps the arm back until it locks the shoulder joint, then uses forward pressure to throw. Implementations Aikido makes use of body movement (tai sabaki) to blend with uke. For example, an "entering" (irimi) technique consists of movements inward towards uke, while a "turning" (?? tenkan?) technique uses a pivoting motion. Additionally, an "inside" (? uchi?) technique takes place in front of uke, whereas an "outside" (? soto?) technique takes place to his side; a "front" (? omote?) technique is applied with motion to the front of uke, and a "rear" (? ura?) version is applied with motion towards the rear of uke, usually by incorporating a turning or pivoting motion. Finally, most techniques can be performed while in a seated posture (seiza). Techniques where both uke and tori are standing are called tachi-waza, techniques where both start off in seiza are called suwari-waza, and techniques performed with uke standing and tori sitting are called hanmi handachi (????). Thus, from fewer than twenty basic techniques, there are thousands of possible implementations. For instance, ikky? can be applied to an opponent moving forward with a strike (perhaps with an ura type of movement to redirect the incoming force), or to an opponent who has already struck and is now moving back to reestablish distance (perhaps an omote-waza version). Specific aikido kata are typically referred to with the formula "attack-technique(-modifier)". For instance, katate-dori ikky? refers to any ikky? technique executed when uke is holding one wrist. This could be further specified as katate-dori ikky? omote, referring to any forward-moving ikky? technique from that grab. Atemi (???) are strikes (or feints) employed during an aikido technique. Some view atemi as attacks against "vital points" meant to cause damage in and of themselves. For instance, G?z? Shioda described using atemi in a brawl to quickly down a gang's leader. Others consider atemi, especially to the face, to be methods of distraction meant to enable other techniques. A strike, whether or not it is blocked, can startle the target and break his or her concentration. The target may become unbalanced in attempting to avoid the blow, for example by jerking the head back, which may allow for an easier throw. Many sayings about atemi are attributed to Morihei Ueshiba, who considered them an essential element of technique. Weapons Weapons training in aikido traditionally includes the short staff (j?), wooden sword (bokken), and knife (tant?). Some schools incorporate firearm-disarming techniques. Both weapon-taking and weapon-retention are taught. Some schools, such as the Iwama style of Morihiro Saito, usually spend substantial time with bokken and j?, practised under the names aiki-ken, and aiki-j?, respectively. The founder developed many of the empty-handed techniques from traditional sword and spear movements. Consequently, the practice of the weapons arts gives insight into the origin of techniques and movements, and reinforces the concepts of distance, timing, foot movement, presence and connectedness with one's training partner(s). Multiple attackers and randori One feature of aikido is training to defend against multiple attackers, often called taninzudori, or taninzugake. Freestyle practice with multiple attackers, called randori (??) or jiy?waza (???), is a key part of most curricula and is required for the higher level ranks. Randori exercises a person's ability to intuitively perform techniques in an unstructured environment. Strategic choice of techniques, based on how they reposition the student relative to other attackers, is important in randori training. For instance, an ura technique might be used to neutralise the current attacker while turning to face attackers approaching from behind. In Shodokan Aikido, randori differs in that it is not performed with multiple persons with defined roles of defender and attacker, but between two people, where both participants attack, defend, and counter at will. In this respect it resembles judo randori. Injuries In applying a technique during training, it is the responsibility of tori to prevent injury to uke by employing a speed and force of application that is commensurate with their partner's proficiency in ukemi. Injuries (especially those to the joints), when they do occur in aikido, are often the result of tori misjudging the ability of uke to receive the throw or pin. A study of injuries in the martial arts showed that the type of injuries varied considerably from one art to the other. Soft tissue injuries are one of the most common types of injuries found within aikido, as well as joint strain and stubbed fingers and toes. Several deaths from head-and-neck injuries, caused by aggressive shih?nage in a senpai/k?hai hazing context, have been reported. Mental training Aikido training is mental as well as physical, emphasizing the ability to relax the mind and body even under the stress of dangerous situations. This is necessary to enable the practitioner to perform the bold enter-and-blend movements that underlie aikido techniques, wherein an attack is met with confidence and directness. Morihei Ueshiba once remarked that one "must be willing to receive 99% of an opponent's attack and stare death in the face" in order to execute techniques without hesitation. As a martial art concerned not only with fighting proficiency but with the betterment of daily life, this mental aspect is of key importance to aikido practitioners.

Aikido Training In aikido, as in virtually all Japanese martial arts, there are both physical and mental aspects of training. The physical training in aikido is diverse, covering both general physical fitness and conditioning, as well as specific techniques. Because a substantial portion of any aikido curriculum consists of throws, beginners learn how to safely fall or roll. The specific techniques for attack include both strikes and grabs; the techniques for defense consist of throws and pins. After basic techniques are learned, students study freestyle defense against multiple opponents, and techniques with weapons. Fitness Physical training goals pursued in conjunction with aikido include controlled relaxation, correct movement of joints such as hips and shoulders, flexibility, and endurance, with less emphasis on strength training. In aikido, pushing or extending movements are much more common than pulling or contracting movements. This distinction can be applied to general fitness goals for the aikido practitioner. In aikido, specific muscles or muscle groups are not isolated and worked to improve tone, mass, or power. Aikido-related training emphasizes the use of coordinated whole-body movement and balance similar to yoga or pilates. For example, many dojos begin each class with warm-up exercises (???? junbi tais??), which may include stretching and ukemi (break falls). Roles of uke and tori Aikido training is based primarily on two partners practicing pre-arranged forms (kata) rather than freestyle practice. The basic pattern is for the receiver of the technique (uke) to initiate an attack against the person who applies the technique—the ?? tori, or shite ?? (depending on aikido style), also referred to as ?? nage (when applying a throwing technique), who neutralises this attack with an aikido technique. Both halves of the technique, that of uke and that of tori, are considered essential to aikido training. Both are studying aikido principles of blending and adaptation. Tori learns to blend with and control attacking energy, while uke learns to become calm and flexible in the disadvantageous, off-balance positions in which tori places them. This "receiving" of the technique is called ukemi. Uke continuously seeks to regain balance and cover vulnerabilities (e.g., an exposed side), while tori uses position and timing to keep uke off-balance and vulnerable. In more advanced training, uke will sometimes apply reversal techniques (??? kaeshi-waza?) to regain balance and pin or throw tori. Ukemi (???) refers to the act of receiving a technique. Good ukemi involves attention to the technique, the partner and the immediate environment—it is an active rather than a passive receiving of aikido. The fall itself is part of aikido, and is a way for the practitioner to receive, safely, what would otherwise be a devastating strike or throw. Initial attacks Aikido techniques are usually a defense against an attack, so students must learn to deliver various types of attacks to be able to practice aikido with a partner. Although attacks are not studied as thoroughly as in striking-based arts, sincere attacks (a strong strike or an immobilizing grab) are needed to study correct and effective application of technique. Many of the strikes (?? uchi?) of aikido resemble cuts from a sword or other grasped object, which indicate its origins in techniques intended for armed combat. Other techniques, which explicitly appear to be punches (tsuki), are practiced as thrusts with a knife or sword. Kicks are generally reserved for upper-level variations; reasons cited include that falls from kicks are especially dangerous, and that kicks (high kicks in particular) were uncommon during the types of combat prevalent in feudal Japan. Some basic strikes include: 1. Front-of-the-head strike (???? sh?men'uchi?) a vertical knifehand strike to the head. In training, this is usually directed at the forehead or the crown for safety, but more dangerous versions of this attack target the bridge of the nose and the maxillary sinus. 2. Side-of-the-head strike (???? yokomen'uchi?) a diagonal knifehand strike to the side of the head or neck. 3. Chest thrust (??? mune-tsuki?) a punch to the torso. Specific targets include the chest, abdomen, and solar plexus. Same as "middle-level thrust" (???? ch?dan-tsuki?), and "direct thrust" (??? choku-tsuki?). 4. Face thrust (???? ganmen-tsuki?) a punch to the face. Same as "upper-level thrust" (???? j?dan-tsuki?). Beginners in particular often practice techniques from grabs, both because they are safer and because it is easier to feel the energy and lines of force of a hold than a strike. Some grabs are historically derived from being held while trying to draw a weapon; a technique could then be used to free oneself and immobilize or strike the attacker who is grabbing the defender. The following are examples of some basic grabs: 1. Single-hand grab (???? katate-dori?) one hand grabs one wrist. 2. Both-hands grab (???? morote-dori?) both hands grab one wrist. Same as "single hand double-handed grab" (?????? katatery?te-dori?) 3. Both-hands grab (???? ry?te-dori?) both hands grab both wrists. Same as "double single-handed grab" (????? ry?katate-dori?). 4. Shoulder grab (??? kata-dori?) a shoulder grab. "Both-shoulders-grab" is ry?kata-dori (?????). It is sometimes combined with an overhead strike as Shoulder grab face strike (?????? kata-dori men-uchi?). 5. Chest grab (??? mune-dori or muna-dori?) grabbing the (clothing of the) chest. Same as "collar grab" (??? eri-dori?). Basic techniques The following are a sample of the basic or widely practiced throws and pins. Many of these techniques derive from Dait?-ry? Aiki-j?jutsu, but some others were invented by Morihei Ueshiba. The precise terminology for some may vary between organisations and styles, so what follows are the terms used by the Aikikai Foundation. Note that despite the names of the first five techniques listed, they are not universally taught in numeric order. 1. First technique (?? (?) ikky??) a control using one hand on the elbow and one hand near the wrist which leverages uke to the ground. This grip applies pressure into the ulnar nerve at the wrist. 2. Second technique (?? niky??) a pronating wristlock that torques the arm and applies painful nerve pressure. (There is an adductive wristlock or Z-lock in ura version.) 3. Third technique (?? sanky??) a rotational wristlock that directs upward-spiraling tension throughout the arm, elbow and shoulder. 4. Fourth technique (?? yonky??) a shoulder control similar to ikky?, but with both hands gripping the forearm. The knuckles (from the palm side) are applied to the recipient's radial nerve against the periosteum of the forearm bone. 5. Fifth technique (?? goky??) visually similar to ikky?, but with an inverted grip of the wrist, medial rotation of the arm and shoulder, and downward pressure on the elbow. Common in knife and other weapon take-aways. 6. Four-direction throw (???? shih?nage?) The hand is folded back past the shoulder, locking the shoulder joint. 7. Forearm return (???? kotegaeshi?) a supinating wristlock-throw that stretches the extensor digitorum. 8. Breath throw (???? koky?nage?) a loosely used term for various types of mechanically unrelated techniques, although they generally do not use joint locks like other techniques. 9. Entering throw (???? iriminage?) throws in which tori moves through the space occupied by uke. The classic form superficially resembles a "clothesline" technique. 10.Heaven-and-earth throw (???? tenchinage?) beginning with ry?te-dori; moving forward, tori sweeps one hand low ("earth") and the other high ("heaven"), which unbalances uke so that he or she easily topples over. 11.Hip throw (??? koshinage?) aikido's version of the hip throw. Tori drops his or her hips lower than those of uke, then flips uke over the resultant fulcrum. 12. Figure-ten throw (???? j?jinage?) or figure-ten entanglement (???? j?jigarami?) a throw that locks the arms against each other (The kanji for "10" is a cross-shape: ?). 13. Rotary throw (???? kaitennage?) Tori sweeps the arm back until it locks the shoulder joint, then uses forward pressure to throw. Implementations Aikido makes use of body movement (tai sabaki) to blend with uke. For example, an "entering" (irimi) technique consists of movements inward towards uke, while a "turning" (?? tenkan?) technique uses a pivoting motion. Additionally, an "inside" (? uchi?) technique takes place in front of uke, whereas an "outside" (? soto?) technique takes place to his side; a "front" (? omote?) technique is applied with motion to the front of uke, and a "rear" (? ura?) version is applied with motion towards the rear of uke, usually by incorporating a turning or pivoting motion. Finally, most techniques can be performed while in a seated posture (seiza). Techniques where both uke and tori are standing are called tachi-waza, techniques where both start off in seiza are called suwari-waza, and techniques performed with uke standing and tori sitting are called hanmi handachi (????). Thus, from fewer than twenty basic techniques, there are thousands of possible implementations. For instance, ikky? can be applied to an opponent moving forward with a strike (perhaps with an ura type of movement to redirect the incoming force), or to an opponent who has already struck and is now moving back to reestablish distance (perhaps an omote-waza version). Specific aikido kata are typically referred to with the formula "attack-technique(-modifier)". For instance, katate-dori ikky? refers to any ikky? technique executed when uke is holding one wrist. This could be further specified as katate-dori ikky? omote, referring to any forward-moving ikky? technique from that grab. Atemi (???) are strikes (or feints) employed during an aikido technique. Some view atemi as attacks against "vital points" meant to cause damage in and of themselves. For instance, G?z? Shioda described using atemi in a brawl to quickly down a gang's leader. Others consider atemi, especially to the face, to be methods of distraction meant to enable other techniques. A strike, whether or not it is blocked, can startle the target and break his or her concentration. The target may become unbalanced in attempting to avoid the blow, for example by jerking the head back, which may allow for an easier throw. Many sayings about atemi are attributed to Morihei Ueshiba, who considered them an essential element of technique. Weapons Weapons training in aikido traditionally includes the short staff (j?), wooden sword (bokken), and knife (tant?). Some schools incorporate firearm-disarming techniques. Both weapon-taking and weapon-retention are taught. Some schools, such as the Iwama style of Morihiro Saito, usually spend substantial time with bokken and j?, practised under the names aiki-ken, and aiki-j?, respectively. The founder developed many of the empty-handed techniques from traditional sword and spear movements. Consequently, the practice of the weapons arts gives insight into the origin of techniques and movements, and reinforces the concepts of distance, timing, foot movement, presence and connectedness with one's training partner(s). Multiple attackers and randori One feature of aikido is training to defend against multiple attackers, often called taninzudori, or taninzugake. Freestyle practice with multiple attackers, called randori (??) or jiy?waza (???), is a key part of most curricula and is required for the higher level ranks. Randori exercises a person's ability to intuitively perform techniques in an unstructured environment. Strategic choice of techniques, based on how they reposition the student relative to other attackers, is important in randori training. For instance, an ura technique might be used to neutralise the current attacker while turning to face attackers approaching from behind. In Shodokan Aikido, randori differs in that it is not performed with multiple persons with defined roles of defender and attacker, but between two people, where both participants attack, defend, and counter at will. In this respect it resembles judo randori. Injuries In applying a technique during training, it is the responsibility of tori to prevent injury to uke by employing a speed and force of application that is commensurate with their partner's proficiency in ukemi. Injuries (especially those to the joints), when they do occur in aikido, are often the result of tori misjudging the ability of uke to receive the throw or pin. A study of injuries in the martial arts showed that the type of injuries varied considerably from one art to the other. Soft tissue injuries are one of the most common types of injuries found within aikido, as well as joint strain and stubbed fingers and toes. Several deaths from head-and-neck injuries, caused by aggressive shih?nage in a senpai/k?hai hazing context, have been reported. Mental training Aikido training is mental as well as physical, emphasizing the ability to relax the mind and body even under the stress of dangerous situations. This is necessary to enable the practitioner to perform the bold enter-and-blend movements that underlie aikido techniques, wherein an attack is met with confidence and directness. Morihei Ueshiba once remarked that one "must be willing to receive 99% of an opponent's attack and stare death in the face" in order to execute techniques without hesitation. As a martial art concerned not only with fighting proficiency but with the betterment of daily life, this mental aspect is of key importance to aikido practitioners.